Proponents of traditional cognitive-processing based treatment models insist that interventions that engage the body but do not explore traumatic memories directly cannot resolve symptoms of posttraumatic stress.Ĭompelling findings from well-designed studies of bottom-up interventions - including trauma-sensitive yoga and clinical neurofeedback - for adults with long histories of limited response to traditional trauma therapies suggest otherwise. Nevertheless, other professionals in the traumatic stress field are highly skeptical of this approach. synchrony between breathing and heart rate.

deep, relaxed (diaphragmatic) breathing, and.To activate this bottom-up process, the following activities could be used:

This happens by resetting trauma-related emotional and sensory states stored within the limbic system and peripheral nervous system. These interventions endeavor to undo trauma’s imprint on the body by directly accessing the limbic system, the feeling center of the brain, and by directly targeting sensory receptors located throughout the body.īottom-up treatment interventions are believed by a growing number of complex trauma practitioners to regulate and adjust the visceral responses associated with complex trauma. Other, more somatically-driven and body-based interventions adopt what has been characterized as a bottom-up approach to trauma therapy.

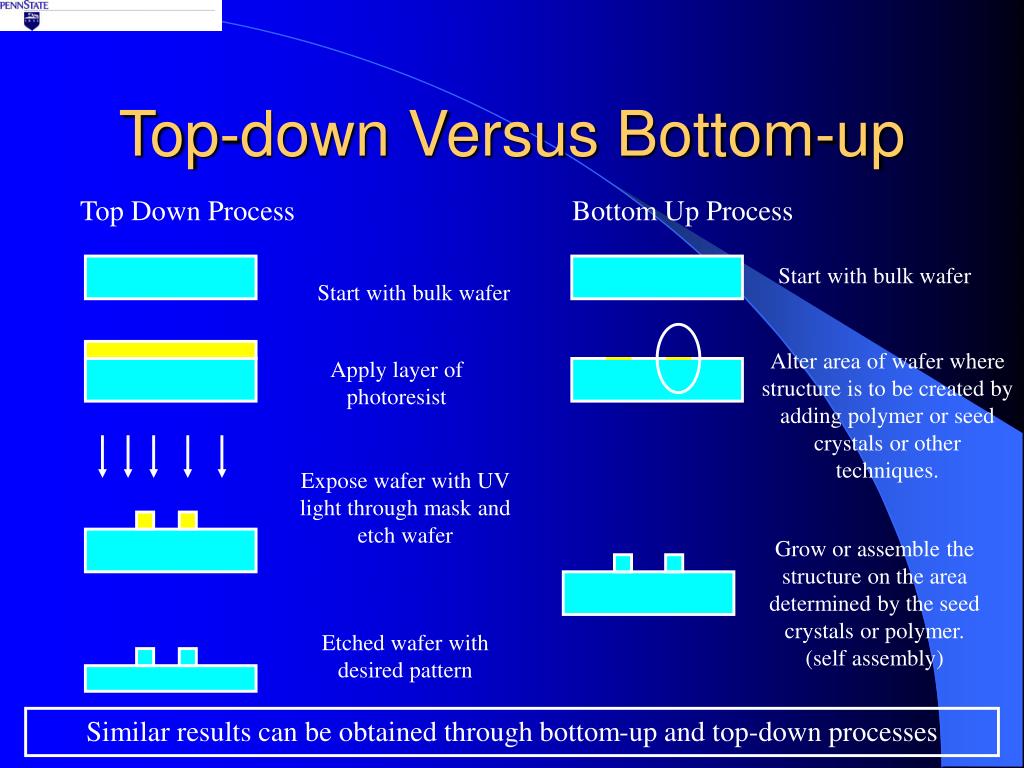

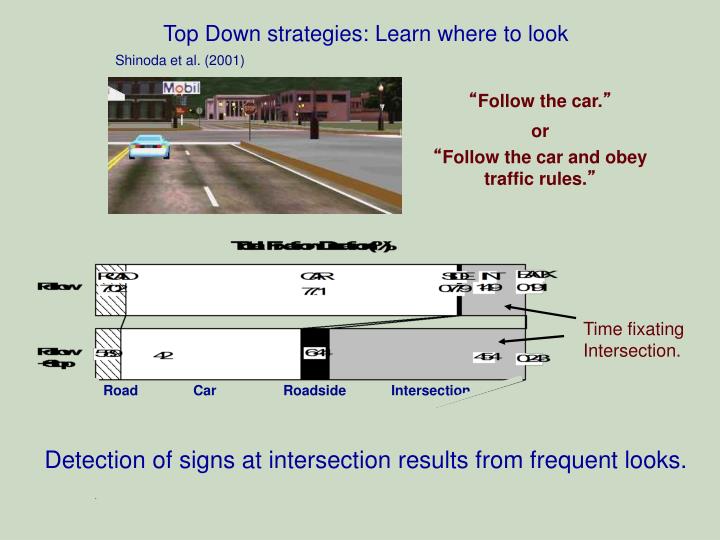

These get reactivated in the face of perceived threat, even and increasingly when the current trigger, while perhaps frustrating, is hardly life threatening and ultimately a false alarm. When this occurs, our distinctively human cognitive controls stop working and cannot be recruited to shut down our more primitive “ fight or flight” response or the many associated sensorimotor survival-driven action patterns that we have learned during past experiences of danger. When the body’s physiological alarm system is activated, the areas of the brain responsible for these higher order executive functions go dark. Joseph LeDoux have theorized that information entering the brain through its primary cognitive processing center-the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex-typically remains stuck in the prefrontal cortex and cannot not reach the emotion regulating centers of the brain. Otherwise helpful cognitive capacities like perspective taking, reason, problem-solving and decision-making, and the capacity for impulse control routinely falter in the face of trauma. Over time, this would reshape a person’s physiological and emotional responses to these experiences in the present.Įxperimental research has demonstrated, however, that the brain’s ability to regulate arousal through cognition becomes compromised, and can even by deactivated, by acute stress. Top-down processing presumes that something similar to a boss-employee relationship exists between the prefrontal cortex and the limbic system: namely, the thinking centers of the brain can activate cognitive controls adjusting the feeling centers of the brain.įollowing this logic, enhanced cognitive regulation would enable a person to alter the relevance of current environmental “stimuli”, things like: Most often this involves efforts to resolve trauma symptoms by working with the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain most responsible for logic and reason. Traditional talk-based psychotherapy, and most cognitively-oriented trauma-focused therapies, are viewed as taking a top-down approach to treatment. Hiding in plain sight, this side doorof the brain may be accessible through use of integrative mind-body techniques, expressive arts-based therapies, and other innovative forms of intervention. However, limitations of both treatment approaches, and the false binary they presume, suggest there may in fact be a third pathway toward recovery from trauma. These terms refer to the emphasis of a given treatment model in targeting two distinct brain regions.

Trauma therapies are often fall into one of two distinct categories: top-down or bottom-up.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)